Starting at the very beginning, Elizabeth Ann Purvis was born in January 1852 to Isabelle & tobacconist Archibald Purvis in Newcastle. She had an older brother called John and a younger sister, and by the 1861 census, the family were living in Elswick, Newcastle with Archibald still selling tobacco and John now aged 16 and working as a druggist clerk. The irony of her father selling tobacco and Elizabeth’s nursing career is not lost on me, though the health implications of smoking were not as well documented in those days.

Tracing Elizabeth in the census records has helped to give a little shape to her family background and thrown up a few mysterious absences! In 1864, the family suffered a tragedy when Archibald died, making Isabelle the head of the household in the 1871 census, with John now a clerk in the local ironworks and Elizabeth an assistant teacher in a ladies school. Strangely, the 1881 census revealed no trace of Elizabeth, perhaps she was nursing or training in London or Manchester though why her name didn’t appear is a bit of a mystery. She also seems to be missing from 1911 census; I sorely wished I could access the 1921 census to track her down one last time!

Nursing Education and Early Career

Anyway, back to Elizabeth’s nursing story and her connection with Middlesbrough. The 1860’s saw the beginning of formal nursing training with the development of private nursing institutions & formal training in hospitals, a system inaugurated by none other than Florence Nightingale. Elizabeth Purvis trained as a nurse as part of this relatively new system at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London and St.Marylebone Infirmary before moving to a position as a sister at the Monsall Fever Hospital in Manchester. It is worth noting that she was a healthcare pioneer in so many ways, not least because she was one of the early members of the Royal British Nursing Association (founded in 1887) and the Matrons Council of Great Britain (established in 1894) during a campaign calling for the registration of all nurses.

Arrival in Middlesbrough and the District Nursing Association

Elizabeth arrived in Middlesbrough in 1889 to take up a nursing position for Dr. John Hedley of Yester House in Marton Road (for which we have a number of building plans in our collections, dating from 1873-1920). The Middlesbrough District Nursing Association (MDNA) was founded a year later with Elizabeth Purvis named as the Lady Superintendent of the Nurses Home; she’d obviously made quite an impression or was she the only one available in the town to take up such a position? The District Nursing movement has an interesting history in itself, the following text taken from the QNI (Queen’s Nursing Institute) website;

‘Before the National Health Service came into being in July 1948, organisers of local district nursing associations were responsible for employing district nurses and paying their salaries, building homes for them to live in, and other expenses. All these local associations undertook fundraising to meet their outgoings. The large majority of these local associations were affiliated to the Queen’s Nursing Institute.

District nursing associations often established ‘provident schemes’, where people would join the association and pay a regular subscription in order to receive nursing care when the need arose.’

In the early days of community healthcare, nurses carried out a huge number of home visits and these brought Elizabeth face to face with the squalid living conditions and dire poverty of the working class population of Middlesbrough. This was a town whose population had exploded exponentially to meet the labour demand of the growing iron and steel industries and the housing provision could barely keep up. By 1891, it was decided there was a desperate need to raise special funds to help the poorer patients who could not afford medical or welfare help. Elizabeth’s working life was spent not only caring for the sick but also helping to provide the most basic of necessities for life, things she could see were lacking and desperately needed for any chance of recovery. As a charitable organisation, the MDNA received monetary donations from local groups and individuals such as businessmen and workers federations as well as donations of such items as clothing, linen, blankets, fruit & vegetables, and meals for patients who were convalescing.

Charitable Works and Welfare Initiatives

As if visiting people in their own homes wasn’t enough to do (she was said to have carried out over 4000 solo visits in her first year in the town), Elizabeth actively campaigned on many issues and administered and promoted a range of charitable funds, which included the following;

- Sister Purvis Convalescent Fund – this aimed to provide a Convalescent Home for patients, with time to recover in pleasant surroundings with good food. One of the convalescent homes was the Coatham Home in Redcar.

- Samaritan Fund – provided dinners for patients who were convalescing in addition to clothing & bedding.

- Fresh Air Fund – this fund sent children for a fortnight into the countryside for fresh air and good food. As part of this, Brooklands Cottage in Carlton-in-Cleveland was purchased in 1927 and provided holidays for mothers and their babies and toddlers (a story we will return to in a later blog so, watch this space!).

- King Edward Memorial Fund – this was set up as a memorial to the late King Edward VII as a convalescent fund to help restore the health & well being of poor people recovering from illness or injury who would benefit from a holiday. The subscribers included individuals, railway society members and local businessmen and was a lifeline to so many before the advent of the NHS and free healthcare for all.

Public Health Challenges

Conditions were tough from the very beginning for Elizabeth, the town suffering from an epidemic of pneumonia in 1888 and one of typhoid fever in 1890-1891 not to mention the highly contagious childhood diseases such as whooping cough, diphtheria and measles, which spread quickly through the overcrowded terraces. This was on top of the terrible physical injuries suffered by the industrial workers. Throughout it all, Elizabeth visited the homes of the sick to administer medical aid and medicines at a difficult time for district nurses; there were no free prescriptions or healthcare and the MDNA was competing with a number of other local institutions reliant on voluntary contributions to carry out their work. Sometimes, it feels as though we really are living in a state of déjà vu; I wonder how Elizabeth would view today’s troubles and issues in light of the relative wealth of the nation as a whole though with one fundamental difference, the NHS?

The following years saw hundreds of new cases of tuberculosis and typhoid reported every month, and thousands of home visits were made by Elizabeth to treat these patients. The need for more nursing help can be seen in the census records; in 1891 there was only one other trained nurse resident alongside Elizabeth at the Middlesbrough Nurses Home but by 1901, the increasing population of Middlesbrough and the large number of tuberculosis cases saw five trained nurses with her in the Nurses Home on Cambridge Terrace. By October 1894, the number of tuberculosis case had reached a new high and it was suggested that an emergency committee needed to be set up to deal with the situation and to which Elizabeth could apply in any urgent case or difficulty.

As well as medical care, Sister Purvis could see the vital role that good welfare played in people’s recovery and avoidance of disease and worked hard to meet this demand. She took responsibility for the introduction and management of several welfare groups including The Women’s Settlement Home, which provided women with a safe place and help to develop their skills of independence, housekeeping and family welfare as well as providing them with leisure activities. She was involved in Girls Clubs, Happy Evenings and she founded the Maternity & Children’s Welfare Centre, roles she carried out on a purely voluntary basis. These groups proved to be so vital to the population that the council took over the responsibility but kept Elizabeth as manager, providing social gatherings, outings & children’s parties among other activities.

Elizabeth not only took care of the sick but she was also very much concerned with supporting the nurses under her supervision. She demonstrated on several occasions that the welfare of nurses was an important matter. In September 1909, Elizabeth Purvis met with the Medical Charities Recuperation Society where she raised the issue of appointing an eighth district nurse to help meet the medical and welfare needs of the population and to support the current nurses. During May 1911 she reported that although the health of the district nurses was maintained, the team was feeling the strain of the difficult winter workload, something current day NHS workers are only too aware of after 3 years of Covid. Her solution was the engagement of a holiday nurse to provide cover and enable each nurse to take the holiday to which they were entitled and had rightly earned. In 1918 when the country was in the grips of rationing, she applied to the Food Control Office saying that the amount of tea allowed by the local Food Committee was insufficient for the needs of the household (Nurses Home). She said after a hard & difficult morning where nurses were unable to take their lunch, they deserved a cup of tea (I would add, at the very least).

Social Reform and Professional Advocacy

Looking in to Elizabeth’s life, she really does feel like a woman ahead of her time. An article in the Evening Gazette of 4/3/1913 records her addressing the Middlesbrough branch of the Women’s Freedom League about her nursing profession. She covered the evolution of the profession and said that until recently the care of the sick was left to religious organisations with the current system of nursing having been inaugurated by Florence Nightingale. Elizabeth said that there was a need for the state registration of nurses, to gain the professional status nurses deserved, a view keenly felt for several years but despite this, every bill for that purpose had met with a lot of opposition. In her opinion, there was little chance of this becoming law until women were franchised and she proved right. The outbreak of World War One and the subsequent involvement of women in the war effort did in deed lead to women being franchised following the end of the war and the state registration of nurses started in 1921.

World War One heaped even more work on the nurses of the MDNA. Cases of tuberculosis were still rife, food rationing was introduced and some nurses were called upon to work in the military hospitals caring for the many soldiers returning with home from the war with injuries. Due to the impossibility of recruiting new nurses, Elizabeth felt an adjustment of the workload was essential and a decision was taken that only the most serious cases would receive care and attention with a degree of self-help recommended for those judged less urgent. The end of the war also saw the huge challenge of the Spanish flu pandemic from 1918 to 1919, which claimed so many lives.

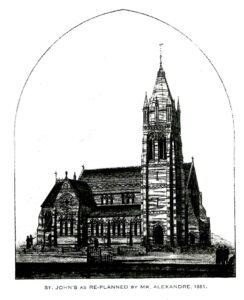

It’s clear from some of the newspaper articles about Elizabeth that her church and faith were an important part of her life, and I’m sure her faith gave her the strength to continue under incredibly challenging circumstances. She was a regular worshipper and a part of a number church councils and I hope there was a suitably big turnout for her funeral, which took place in the beautiful St John’s Church, on Marton Road.

Legacy and Death

Sister Elizabeth Ann Purvis died on 25th August 1928, after lifetime dedicated to the service of the town, right up until her death. Throughout her time in Middlesbrough, doctors and medical practitioners acknowledged the care and compassion she had shown and I hope they also admired and recognised her knowledge and expertise. She was equal to them in so many ways, needing to win people’s trust in order to treat them effectively in their homes. Elizabeth enjoyed several mentions in the MDNA minutes, acknowledging her hard work and commitment and her obituary includes the statement:

“The death of Miss Purvis is not only a great loss to the town, the MDNA, the working people, and the poor, but also it is to the medical men …”

Her funeral was held on 27th August following her death on 25th August, at St John’s Church and she is buried in Linthorpe Cemetery, a grave I hope to track down in time to pay my respects to a life well lived.

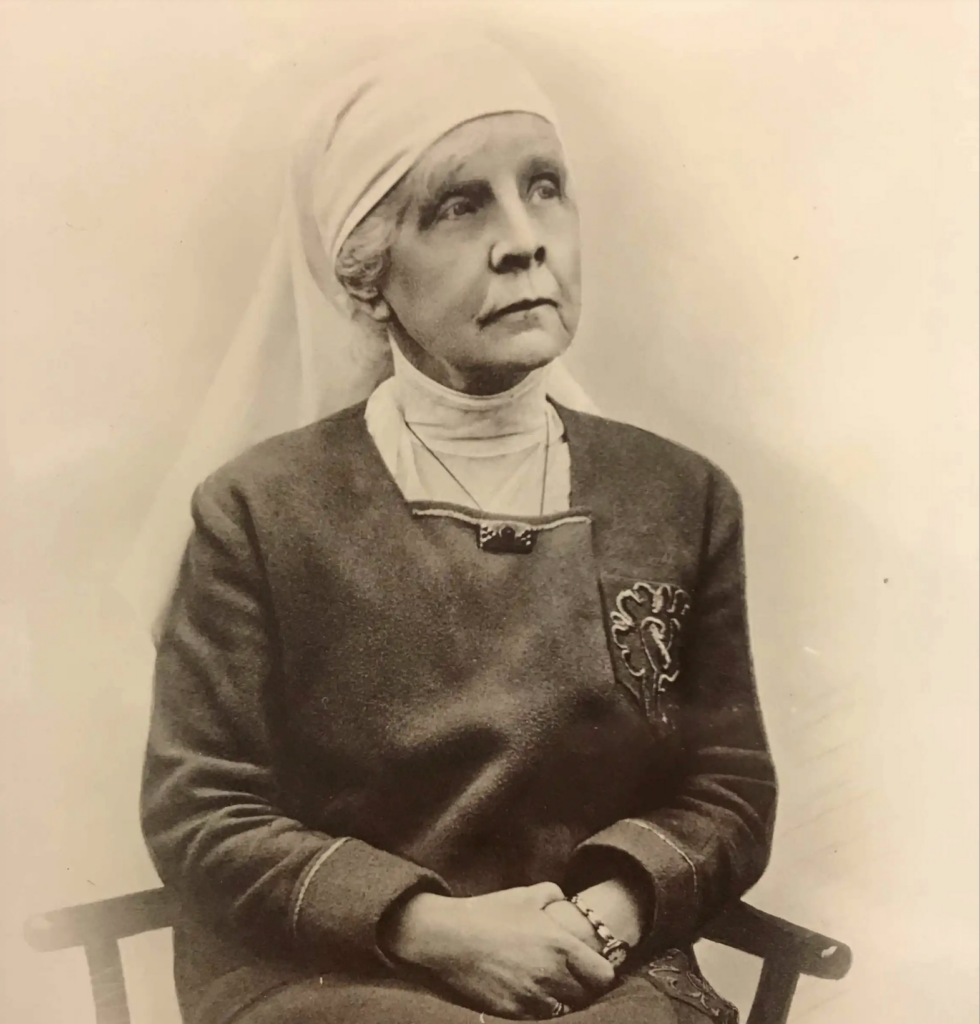

One newspaper article marking her death mentioned her distinctive purple cloak, the sight of which must have brought such relief to so many in times of great suffering. I look at Elizabeth’s photograph, the only one we have of her in the archives, taken 6 years before she died and see a woman of huge strength, stamina and grace, somebody who gave nearly 40 years of her life to the people of Middlesbrough, who never passed judgement but who helped where she could and who showed such duty and dedication. She saw the best and worst of humanity, and dealt with it all to the best of her ability while actively campaigning for improvement and change. She truly was our very own northern Florence Nightingale.

Written by Sharon Goodman (Teesside Archives Volunteer) and Chris Corbett (Teesside Archives Community Engagement Officer).

Researched by Sharon Goodman (Teesside Archives Volunteer).